They were built to be summer cottages: a place to slip away to fish and relax by the lake with the family during the summer months. Those were the days of rustic camping; it was the 1960s and getting away with the family meant parents and kids piling in the station wagon and heading outdoors. To these first families of Smith Mountain Lake, it was upscale camping in cottages; simple homes provided a roof and floor to house beds and sofas, and dining usually occurred outside on screened porches and decks overlooking the water. It was peaceful and quiet, and life was so simple. You packed your groceries and headed to the lake, for a weekend, for a week, or for the entire summer. It was the best of times.

They were built to be summer cottages: a place to slip away to fish and relax by the lake with the family during the summer months. Those were the days of rustic camping; it was the 1960s and getting away with the family meant parents and kids piling in the station wagon and heading outdoors. To these first families of Smith Mountain Lake, it was upscale camping in cottages; simple homes provided a roof and floor to house beds and sofas, and dining usually occurred outside on screened porches and decks overlooking the water. It was peaceful and quiet, and life was so simple. You packed your groceries and headed to the lake, for a weekend, for a week, or for the entire summer. It was the best of times.

Before The Lake

Before The Lake

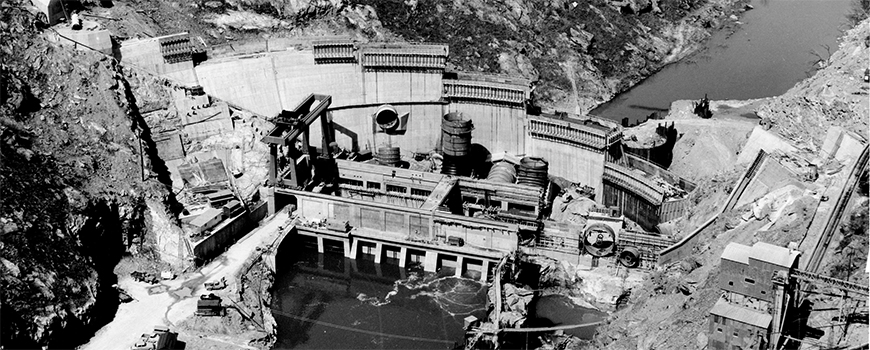

Smith Mountain Lake started with three waterways and Southwest Virginia’s growing demand for electricity. Appalachian Power decided to build the dam and create the lake in 1963. It was an unusual lake that developed—not a typical round one. Smith Mountain Lake came together from three tributaries: the Roanoke River, the Blackwater River and Gills Creek. These three waterways filled into a main body that encompasses more than 500 miles of shoreline. The water filled in over the rural farmland that was flooded once the dam was set and finished in 1963. By 1966, the lake was formed. The shoreline and land around it was mostly untouched as the water slowly rose to full pond. A few trailers and lake cabins made up the modest homes that sat on the waterfront in those days.

More were built in the following decade, making the lake a true rural retreat. From these simple beginnings, a variety of interests surfaced.

Fishing, camping and boating topped the interest of locals. Everyone wanted to be involved. A lake in southern Virginia? No one knew what the whole endeavor would become. Locally, it was naturally a hot commodity the minute Appalachian Power Company released the land for sale. Then farmers started selling their land around the lake. Everyone wanted their little piece; it was the Wild West in Southwest Virginia. Lots sold before the water filled in went for $500 to $1,000, whereas the ones sold just after the lake filled started around $4,000. “Grab your parcel and build your place” was the reigning motto.

Many new lot owners did just that. My husband and I both grew up summering on the lake in our family cabins. Our parents and their friends bought kits to build their cabins or drew rough plans and had the lumber delivered to the site. A few of the cabins were factory-built and transported to the lot with decks and porches attached to them once they were placed. Weekends were for fishing, camping and raising the timbers. If that wasn’t your forte then there were plenty of eager carpenters. Mostly these homes were built by hand by homeowners and local carpenters on site, and that gave them the charm that endures today. Some were trailer homes or little cabins framed by hand with the roof trusses delivered to the site and nailed together by brothers and fathers, but each one is unique: they were individualized by each family’s particular vacation life philosophy. This is the way we roll.

It All Started With The Lots

It All Started With The Lots

These early lake dwellers bought lots from Appalachian Power and from farmers-turned-real estate agents who sold their land surrounding the lake by carting prospective buyers down dirt roads, sometimes in the back of a wagon pulled by a tractor. There was little gravel and no pavement leading to the water parcels. If the mud was bad, you needed a Jeep or a tractor to get there. These salesmen took you down rural roads, preferably in good weather, and showed you the land. There were white spray-painted lines in the field or stakes with bright orange ribbons flying in the wind. “That’s where your water will start,” they would pitch to the businessmen, doctors, and local workers who longed for a little country getaway.

Now these treasured gems are in the second generation. The kids who spent summers roasting hot dogs on camp fires and swam for hours in the dark cold water full of submerged trees are inheriting the places. These youngsters grew up on Smith Mountain Lake; they learned to fish and water ski there. It was quite a way to learn these skills; as you boated in those days you watched out for pieces of old red barns floating in the water. Since the farmland bought by Appalachian Power was then vacated by the owners, it contained old, empty buildings as well as shrubs and trees. The land was flooded just as it sat—complete with farmhouses, barns, outhouses, sheds and vegetation. Anything that couldn’t be hauled away was left to slowly be immersed as the lake filled as the waters rose.

Skiers became adept at zigzagging to avoid hitting floating boards, tree limbs and logs as they flew all over this remote lake behind a little ski boat or canopied pontoon. Eventually, there were ski courses built for the ones who became experts, because there was plenty of remote space on the water to place them. Old milk jugs anchored down at just the right spot made for daring turns and jumps in order to avoid colliding with them. They were impressive early in the morning when the lake was quiet and the only sound was the boat engine humming as it pulled the skier along. Ski gloves and even wetsuits were the dress on cold days. It was such a rush when you could ski the whole course without hitting a buoy or missing one. The big wooden jumps were for the real experts.

Skiers became adept at zigzagging to avoid hitting floating boards, tree limbs and logs as they flew all over this remote lake behind a little ski boat or canopied pontoon. Eventually, there were ski courses built for the ones who became experts, because there was plenty of remote space on the water to place them. Old milk jugs anchored down at just the right spot made for daring turns and jumps in order to avoid colliding with them. They were impressive early in the morning when the lake was quiet and the only sound was the boat engine humming as it pulled the skier along. Ski gloves and even wetsuits were the dress on cold days. It was such a rush when you could ski the whole course without hitting a buoy or missing one. The big wooden jumps were for the real experts.

There were not many marinas in those days, so a trip for gas was often a long one. The original marinas bore little resemblance to those today. They looked like small cabins halfway up the hill with a hose dangling from an old pump on a dock. Their names reflected their various owners or the family that once owned that land: Lumpkins, Dickey Dill’s Place, Indian Point, Smiths, Paradise Marina. Some of these gas spots are now long gone, but a few of the cabins remain. They have been updated and are used as homes now. Their character reflects the unique history of the businesses and families that once existed there.

And so, some of these early cottages remain: They are the history of the lake. These summer homes tell the story of the past five decades, and reflect that the more things change, the more they stay the same. Filled with relics of the 60s and 70s, they are the throwbacks even when they have been carefully kept and renovated by the next generation of the family. Many of these first families have strived to keep the same feel.

And so, some of these early cottages remain: They are the history of the lake. These summer homes tell the story of the past five decades, and reflect that the more things change, the more they stay the same. Filled with relics of the 60s and 70s, they are the throwbacks even when they have been carefully kept and renovated by the next generation of the family. Many of these first families have strived to keep the same feel.

Even the subdivision names tell stories: Merriman Point on the Roanoke River arm was purchased by a local doctor who then sold the lots to his partners and colleagues at Roanoke Memorial Hospital. It was given the nickname “Penicillin Point” because it was known as the place to go if you needed a doctor. Shenandoah Shores was purchased by the CEO of Shenandoah Life Insurance Company who sold lots to the employees. He gave it the name Shenandoah Shores to reflect its history; he sold the land to his employees as a perk. He held a lottery to make it fair. You got to choose your lot in order—those who drew the higher numbers eagerly awaited their turn to purchase a piece of this beautiful land that sat high on a hill of the Blackwater River overlooking the slowly growing lake.

Francis Point was named for the local real estate developer who bought acreage up on the Roanoke River. Once the grandfather purchased the land, a slab was poured and a cottage built overlooking the wide mouth of the Roanoke River. The years moved along and a swimming pool was added; then a bunkroom, patio and a firepit to hold the growing family and their friends. The family still owns that house today as the cove behind it slowly fills with neighboring houses.

Dinner Bells, Hammocks and Adirondack Chairs

Dinner Bells, Hammocks and Adirondack Chairs

Second-generation homeowners work hard to keep up these family lake homes, preserving the old-time feel and traditions and making modifications only when necessary. One such homeowner talks about her family’s labor of love. “We want to do [the work]. We want this place and this lifestyle to be there for our kids, just as our parents built it for us. In fact, I just got back from the lake this morning. We are building a new dock; it’s time—the first one is over 40 years old. We want to carry the tradition along,” she says.

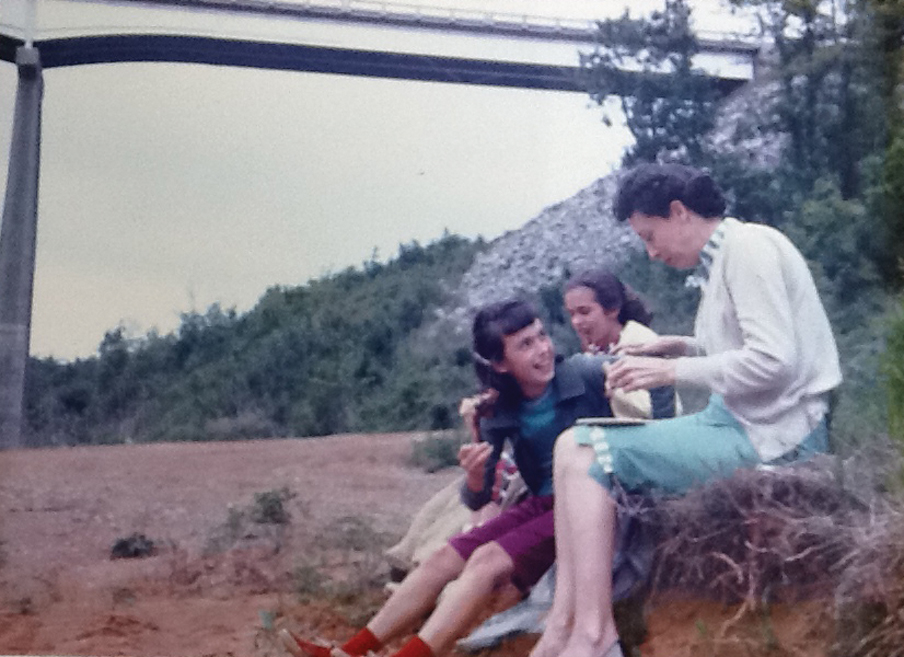

Most families have kept as much as possible the same to convey the original feeling of the lake. A place to gather and relax is the aspiration, though it’s busier now with more homes and boats on the water. It’s easier to get provisions with Westlake and several shopping centers, but once you are in one of these charming cottages, you are transported back to a simpler time. These houses have just what they need to feel like home. They offer the basics, with each one showing the unique touches of that family. Hooked rugs or sisal floor coverings, lots of quilts and blankets in the bedrooms, porch swings, Adirondack chairs, and hammocks in the yard make them inviting spots. Firepits are built of stone for roasting marshmallows and burning up driftwood that floats up on shore. From dinner bells outside the door to the photos on the wall, these relics tell the stories of the early days at the lake. Most old homes display a map of the lake. These maps are often dotted with markings to show how to get to a friend’s house or where is the closest place for gas. Pictures show how houses grew up out of the ground—first the lot before the house, then several of the house being built a stick at a time. One friend recalls packing a lunch and going to the site on Saturdays with her dad and her sister. As he worked on the house, she and her sister played tag between the wall studs.

My husband recalls heading to the lake in the station wagon with his siblings. Before their house was built—sketched on paper by his father and stick-built by a local carpenter—they camped. Dinners were hotdogs or hamburgers on a small grill. There was a port-a-potty for the girls behind the shed. Life was basic. Once the cabin was complete, there was still that matter of the yard. The house sat on top of the hill and they needed a path to the lake. Thus, their father saw easy, free labor in his three sons so he designed a walkway of railroad timbers and gravel for them to build on weekends. “My brothers and I nicknamed it the Burma Road one day as we slowly lugged all that the heavy wood and gravel down the hill towards the water. There was always a good deal of wood and stone to be hauled and placed before we could swim and roam free on the weekends. We skidded lots of wheelbarrow loads of rock down a slippery hill over the years,” he says.

As one friend recalls, “Back then, there was nothing around us. Rocky Mount was the closet grocery store. My mom made friends with the local farmers so she could buy vegetables and produce. We always ran for the boat when Dad needed to go get gas. The marinas had penny candy and that was a big treat.”

As one friend recalls, “Back then, there was nothing around us. Rocky Mount was the closet grocery store. My mom made friends with the local farmers so she could buy vegetables and produce. We always ran for the boat when Dad needed to go get gas. The marinas had penny candy and that was a big treat.”

These are the people who pioneered SML; it became what it is today because of them and their belief that a little summer cabin on the lake represents the best of life. These trendsetters bought lots in a field and built houses based upon what they were told would happen: a lake would appear on the edge of their lot in a few years. Looking back on 50 years, this is how the lake came to be the wonderful community that it now is. Their vision and foresight created many precious places there to unwind and enjoy the beauty of the Blue Ridge Mountains. A lake in the mountains has to be one of the finest gifts nature and man have made together.

Next time you are out on the lake, take a moment as you boat along and notice the small cottages along the lake. In between the big, modern houses, these hidden gems portray the history of the families who started the lake life that we all love today.